Background

The reason to collide gold ions (whose nuclei consists of 197 protons and neutrons) instead of more elementary particles is to generate a state of matter of deconfined quarks and gluons - Quark Gluon Plasma - and study it. This new state of matter requires a density that can only be reached by colliding heavy ions. One of the smoking guns for QGP creation is the observed change in particle production compared to proton + proton collisions. One of such signatures is an enhanced production of protons. We can study particle production in the plasma by observing how a parton (quark or gluon) fragments (decays into stable particles like protons, neutrons, pions, kaons,...) in the presence or absence of the QGP. Luckily, highly energetic jets occur naturally in particle collisions. We can leverage such jets and select the ones that traversed the medium to study them. The challenge is to find the jets and to identify their particle composition.

The present study combines modern jet reconstruction algorithms and particle identification (PID) techniques in order to study the enhancement of proton/pion ratio at mid transverse momentum observed in "head on" gold(Au) + gold(Au) collisions at 200 GeV center of mass energy.

Particle Accelerators

The data used in this analysis comes from millons of particle collisions generated in the - 2.4 miles circunference - Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider located at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Long Island, New York. This massive collider uses a series of super conducting magnets to steer clouds of charged ions to circulate along a pipe and accelerate them until they reach 99.99% of the speed of light. The accelerator's electric and magnetic fields are tunned so as to compress the cloud of charged ions into a stable beam made of buckets of ions. Each bucket is ~15 microns wide in the transverse direction and ~20 cm long and contains up to 10^9 ions.

Heavy Ion collisions

Gold ion collisions are achieved by having two beams circulating alongside each other but in opposite directions. The beams are steered at particular places in such a way that their trayectories intersect. Every now and then a head on collision happens (depending on the collision's cross section and the accelerator luminosity ). The QGP created promptly decays into thousands of partciels that fly away form the collision vertex like a firework. These are the particles that experimentalist have access to.

A series of detectors surround the collision vertex. These detectors trigger interesting events (one with a highly energetic jet, for example) to be saved to disk for further future analysis. The data for the present analysis was recorder at the STAR detector which has full azimuth coverage and can record particles energy as well as charged particles trajectories and time of flight (time it takes for a particle to reach the detector from the collision vertex) Experimentalist are left with the daunting task of looking for signatures of the QGP by analysing millions of collisions with thousands of tracks on each.

Gold - Gold atom collision transverse view

Simulation of 1000 charged particles comming out of the collision vertex. This is the transerse view in the direction of the beam axis

Proton - Proton collision transverse view

Simulation of 10 charged particles comming out of a more elementary proton vs proton collision

Jet finding under high background conditions

It is clear from the picture above that finding jets (collimated stream of particles) among all the tracks present on a gold atoms collsion is like finding a needle in a haystack. Fortunatley, fast jet finding algorithms capable of dealing with the collision's background have been developed. The FastJet framework includes several such recombination algorithms. Particles in a collision are distributed in a 2D grid of azimuth (φ) and pseudorapidity (η) (think angle from beam axis). Jet recombination algorithms look for clusters of particles by finding each particle's nearest neighbor in (φ,η) space. The particles' momentum (or its inverse) are used to weight their distance in order to favor (or disfavor) clustering highly energetic particles first. The algorithms iterates by merging (4 vector adition) the pair of particles that are closest. The FastJet authors managed to use a clever trick by contructing Voroni diagrams (N ln N operation) in (φ,η) space and then just look for the nearest neighbor in the adjacent cells [as described in their paper]. which allows their algorithms to run in N ln N time instead of . This is crucial in order to be able to use such algorithms to find jets in millions of collisions with thousands of particles each in a non prohibitive amount of time.

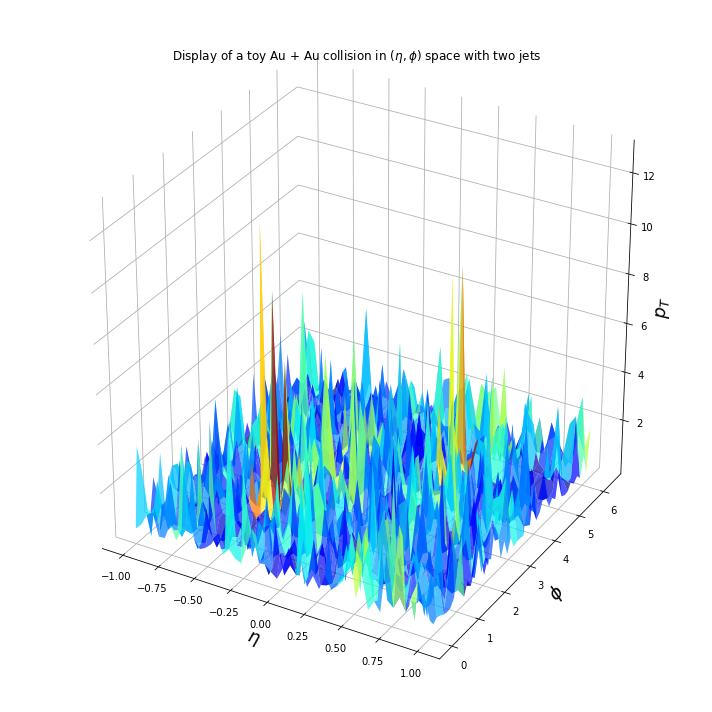

Toy simulation of a gold - gold collision and two jets

Simulated Gold - Gold collision in (φ,η) space (z axis is the transerse momentum). Two jets back to back in azimuth can be observed on top of the heavy ion collision background

Particle identificaton in nuclear physics

Our final goal is to compare proton and pion production in jets traversing the QGP medium and jets fragmenting in vacuum. We use several particle's features to achieve this: momentum, time of flight, energy loss in the TPC gas chamber and charge. For each momentum slice we define two composed variables that allow us to observe different clusters of particles. Each cluster corresponds to a different kind of particle (proton, kaon, pion, electrons, muons). The clusters' distributions start to merge with increased momentum. We use a fit to a 2D distribution (Gaussian * Student t) to be able to distinguish the clusters statistically.